Is it just 'chicken fat' post-mortem clotting that the embalmers are seeing?

A reply to Dr Eric Burnett MD

Dr Eric Burnett MD is a specialist in Internal Medicine at Columbia University Medical Center. After the release of Died Suddenly in November 2022, he posted on Twitter a short video in the first part of which (up to 1:06) he claims in effect that the material being found by the embalmers is nothing more than normal ‘chicken fat’ post-mortem clots. I transcribe what he says below, but taking a listen adds something also.

He goes so far as to claim, without providing any evidence, that the embalmers are engaging in deliberate deception when they say that the material they have been pulling out of bodies is new:

Burnett: All these really graphic images of clots that they supposedly pulled out of bodies.. and according to them this is all very new, this has never happened before - except, that's a lie.

His thesis is that the material is not new at all, but is normal clotting. He continues:

[0:12] So blood can clot after you die and there are ways that we as medical professionals can determine between antemortem clots - those are clots that are formed before death - and postmortem clots - those are clots that form after death. Now I found this great summary slide on Twitter that goes through all the differences between antemortem and postmortem clots.

The slide was posted on Twitter by the human pathologist Judy Melinek MD in August 2021, with no reference:

She has since made it clear that he prepared the slide herself as a teaching aid. (I had of course not suggested that Dr Burnett himself was responsible for the slide which, after all, he admitted to having ‘found on Twitter’. He is responsible for the use he makes of it).

Burnett apparently felt that he could rely on the information in this slide as a basis to give his professional opinion about the material being encountered by the embalmers. Post-mortem clots are stated in the slide to be ‘gelatinous, soft and rubbery’, and accordingly Burnett continues:

[0:31] Now if you look at postmortem clots just with the naked eye, they are gelatinous and they are rubbery, and if you listen to the embalmers on this documentary, that's exactly how they are describing these ‘new strange’ clots that they are finding..

But is this true? Do the embalmers describe this material as ‘gelatinous’ on ‘Died Suddenly’?

At 9:43, embalmer Richard Hirschman, holding a sample preserved in 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (the specific product he uses is here),

describes it as ‘white, fibrous stuff’ (the browning is from its preservation). It certainly does not appear to be gelatinous.

At 11:27, funeral director John O’Looney says his embalmer pulled this:

out ‘as one piece, one elastic piece’. O’Looney said ‘it looks like calamari’.

At 12:07, embalmer and funeral director Chad Whisnant says that he had never before seen these 'long, white, fibrous.. different..'.

At 13:35, embalmer, funeral director, and Chief Deputy Coroner Wallace Hooker CFSP MBIE described the material as ‘white fibrin structures’. His precise meaning is not yet clear to me. Fibrin plays a key role in normal clotting: in the healing of wounds, in venous thrombi (blood clots), and in post-mortem blood coagulation. But since he believes this strong white material to be novel, I am not sure why he would assume that they would be formed primarily of fibrin. In another interview [at 3:45], Hooker referred to them as ‘white fibrous structures’, and possibly this is all he meant to say in his Died Suddenly interview.

At 14:23 an embalmer of hidden identity referred to 'fibrous mass clots'. At 16:54 there is another reference to ‘fibrin structures’, by another person of hidden identity.

At 17:20 Richard Hirschman invites his interviewer to handle a sample. They agree that it is like a rubber band. (It should be noted in passing that this sample had been preserved in formalin, which may have affected its physical properties.)

None of the embalmers describe the material as gelatinous. I believe Dr Burnett is mistaken on this point.

He continues:

one guy even says that they feel like calamari; the postmortem clots typically take the shape of the blood vessels they are in, and that's exactly how those embalmers describe these new-fangled clots that they are finding, they are pulling out these perfect casts of blood vessels made out of these new clots. So this is what a common postmortem clot looks like:

and displays [0:58], enlarged, the illustration of postmortem clot from Judy Melinek’s slide:

What is shown is the type of post-mortem clot, described further below, where the blood, before it coagulates, separates by gravitation into distinct red blood cell and plasma sections.

Burnett then showed an image from Died Suddenly (at 14:21):

and this is what one of their ‘strange new’ clots looks like:

and asked, rhetorically:

notice any similarities here?

and rested his case, which he summarised at the end of his video (2:03):

So just to synopsise, blood clots can form postmortem, they are nothing new and the embalmers in this video are not medical doctors, not experts in blood clotting, not experts in vaccines, and they offer not a single shred of evidence to back up any one of their claims.

Burnett’s argument in outline

Dr Burnett’s argument has two poles:

A) The material being found by embalmers has several features in common with normal postmortem clots. Therefore (it may be taken as implied), there is high probability that these are in fact normal postmortem clots.

B) The embalmers have brought forward no evidence that these are anything other than normal clots.

His conclusion may be stated as:

C) These appear to be normal postmortem clots, and there is no reason to suppose that they are anything else.

A) Claimed commonality of features

According to Burnett’s account, the embalmers’ description of the material they are finding coincides with postmortem clots in the following respects:

A1) They are both gelatinous.

A2) They are both rubbery.

A3) They both take the shape of the blood vessel they are in, and can be pulled out intact as a cast.

A4) They have the same or similar visual appearance.

Taking these in turn:

A1, A2) Are they both gelatinous, and both rubbery?

As I have shown above, the embalmers do not describe their material as gelatinous in Died Suddenly, nor do they do so in other interviews I have watched (some of which I have previously transcribed in part). Dr Burnett is surely mistaken on this point.

Richard Hirschman and his interviewer agreed that the material they were handling was like a rubber band, which is certainly rubbery. But it should be noted that the sample had been preserved in formalin, which may possibly have significantly affected its physical properties.

Postmortem clots are described as ‘gelatinous, soft and rubbery’ on Dr Melinek’s slide. But is she correct on this point? And if she is, what does she mean by ‘rubbery’? She told me (personal communication) that postmortem clots become rubbery after they have been in formalin or chilled for a long time. It follows that her description ‘rubbery’ was therefore meant to apply only to a subset of postmortem clots. Dr Burnett, taking a Twitter slide as the basis for his analysis as he admits, has taken the information there at face value, and missed this finer distinction between categories of postmortem clot. To establish an identity on this basis with postmortem clots, he would have to show that the material had in fact been pulled out of bodies that have been in refrigeration a long time, or had already been changed by contact with formalin. He has not done so, and it seems very doubtful that he would be able to do so, since the embalmers have testified that they have found this material in the bodies of people very recently deceased (see here at 10:40 and here at 18:50), and Hirschman has explained (12:25) that in one of the cases shown in Died Suddenly, he pulled the material out before any embalming fluid had touched the body.

Further, ‘rubbery’ is not a very precise descriptor. I can imagine, to take a homely example, that if a dessert jelly were left on a table for a week or two it could become increasingly rubbery in texture. But would it gain much of the strength of rubber? Could one pull 33 inches of it out of a sheath against friction in one piece, as Richard Hirschman has pulled out a 33 inch length of the material he is finding (out of a single incision in the external iliac vein)? Hirschman himself has said (6:54) that ‘chicken fat’ clot can be ‘kind of rubbery’, his intonation suggesting that this was true only in a certain sense. He went to on to say that the pieces tended to be small and were reminiscent of the yellowish fat that can be found on chicken meat. And he sent me this picture:

which is a far cry from this long piece of the material, for example, that Hirschman pulled out of the leg of the deceased in September 2021:

Wallace Hooker described the material he has found as ‘really tough’, John O’Looney as ‘very tough, and elastic’, Richard Hirschman as ‘pretty strong, not weak at all’. Is the same true of postmortem clots, even when the body has been in refrigeration for a long time? Could liquid blood be transformed into a strong tough solid material after death, when only residual metabolic processes continue? Or does it simply coagulate into something more like jelly?

Postmortem clots have been described as gelatinous in the literature, for example in Robbins et al, ‘Basic Pathology’ (7th edition, p. 92). Note also that it is described as yellow not white:

Similarly, post-mortem clots are described as ‘jelly-like’ in Knight’s Forensic Pathology (3rd edition) in a section on pulmonary embolism, so that the immediate reference is to clotting in the lung. The separation into ‘chicken fat’ plasma clot and dark red-cell clot by gravitational sedimentation is something that happens ‘often’ - and therefore not always:

In his January 2022 interview with Jane Ruby, Hirschman contrasted the consistency of the material he is finding with normal blood clots:

Typically [4:21] a blood clot is smooth, it's blood that has coagulated together, but when you squeeze it or try to pick it up it generally falls apart.. you can almost squeeze it between your fingers and almost get it back to blood again.. but this white fibrous stuff is pretty strong it's not weak at all, you can manipulate it, it's very pliable it's not hard.. it is not normal..

Likewise, Dr S.M.H.M.K. Senanayake, a Sri Lankan consultant Judicial Medical Officer described in the Ceylon Medical Journal (2016) how the plasma (‘chicken fat’) part of separated post-mortem clot can be pressed (crushed) with the fingers and turned back to liquid:

In contrast, Hirschman told Ruby in the same interview (7:39):

I could literally rinse these clots, rub the blood off of them, and this white stuff holds strong. It does not dissolve.

A3 Do they both take the shape of the blood vessels they are in?

John O’Looney has said [1:50] that the ‘clots’ his embalmer has encountered ‘take the shape of the vessels they are growing in’.

Knight et al say (p. 341) that post-mortem clot forms a cast of the branches, if somewhat shrunken, and add the further information that it can be pulled out of vessels, implying at least a modicum of internal cohesion and tensile strength:

The embalmers are also able to pull out the material they are finding as a kind of cast of the vessels they were situated in.

It probably follows that neither material adheres strongly to the vessel walls, since if it did, it would hardly be possible to pull it out intact.

I have however found no reference to long pieces of normal post-mortem clot being pulled out intact, comparable to the 33 inch long structure that Hirschman pulled out in September 2022:

A4 Do they have the same visual appearance?

Dr Burnett claims that the material that the embalmers have been finding looks similar to chicken fat clot:

He must presumably have been unaware, however, that the image on the right comes from a veterinary textbook, namely McGavin and Zachary, ‘Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease’, p. 565.e1, E-Figure 10-5 (also online online in an earlier edition as Web Fig. 10-4)):

and the ‘chicken fat’ arterial cast is taken from a dog. This obviously invalidates his comparison, since he is claiming that the embalmers’ material is human post-mortem clot, not canine clot. It would be for Dr Burnett to demonstrate that human and canine post-mortem appearance are similar in appearance, if he can do so.

The accompanying text indicates that the cast came from a dog’s heart and connecting vessels:

The image on the left, in contrast, does not have a large mass at the centre corresponding to one of the large chambers of the human heart. So again, there is little real comparison between the two.

The image on the left also has some fine strands at the top left and bottom left for which there is no counterpart visible in the image on the right.

Frequency of occurrence of ‘chicken fat’ clot

The text accompanying the image of the canine clot explains that the formation of ‘chicken fat’ clot depends on the erythrocyte (red blood cell) sedimentation rate (ESR) among other factors:

In animals at least, it occurs only occasionally, except in horses (p. 565.e1):

Returning to human post-mortem clotting, Jackowski et al (‘Postmortem imaging of blood and its characteristics using MSCT and MRI’, 2005, p. 239) explain that clotting and sedimentation can occur in parallel. Fast clotting and slow sedimentation will result in more homogenous clots, slow clotting and fast sedimentation in clots with distinct upper and lower regions:

The autopsy appearance of the post-mortem clots they found varied from the colour of black currant jelly to that of red current jelly. They showed none that were white or yellow:

Uekita et al (‘Medico-legal investigation of chicken fat clot in forensic cases: Immunohistochemical and retrospective studies’, 2008, p. 138) state (p. 142) that chicken fat clot is observed in most chronic death cases, but not in acute death cases, because of fibrinolytic activity (the breaking down of fibrin) in the latter:

although they go on to say that there are exceptions to it being absent in acute cases.

Hansma et al (‘Agonal thrombi at autopsy’, 2015, p. 142) agree that chicken fat clot occurs in chronic cases, but argue that it begins to be formed in the agonal period before death:

True post-mortem clots, on the other hand, and in their view, are like either red currant jelly or black currant jelly:

To summarise, post-mortem clot does not occur at all in some bodies, and when it does, it may be homogenous, or only partially separated, and thus near black or red in colour.

Colour

The canine ‘chicken fat’ clot that Dr Burnett used for his comparison looks to be more or less white in colour. The literature, however, states (see above) that in humans this type of clot is yellowish, or possible straw-coloured. The reason for this is that human blood plasma (the upper section in the photo):

normally appears yellow or straw-coloured:

because, it is often said, it contains bilirubin:

which is a brownish yellow pigment. With regard to the scientific literature, a paper in Nature from 1946 states that the yellow colour in serum (plasma without the clotting factors) is generally assumed to be caused mainly by bilirubin:

The presence of bilirubin in human plasma must be at least a factor in the yellow colour of human plasma ‘chicken fat’ clot.

Dogs, however, have only 0-0.1 mg/dL of indirect (unconjugated) bilirubin in their blood:1

compared to 0.2-0.8 mg/dL for humans:

which may help to explain why the canine ‘chicken fat’ clot in the image used by Dr Burnett does appears whitish rather than yellowish.

This further invalidates his comparison of the two images. If he had used a photograph of normal human ‘chicken fat’ clot, a difference in colour would I think have been apparent.

Location

Uekita et al state that ‘chicken fat’ clot is sometimes found ‘in the heart and large blood vessels’ in autopsy cases:

raising the question as to whether it occurs at all in smaller vessels. Their one illustration is of chicken fat clot in the right atrium. It is distinctly yellowish in colour:

They took ‘chicken fat’ clot samples only from the heart (p. 139):

With reference to post-mortem clotting in the lung, Knight et al say (p. 341) that it is ‘less evident in peripheral branches’:

(In passing, the description of post-mortem clot as pouring out of vessels points to its soft gelatinous character. The embalmers’ material seems to be much too solid to pour.)

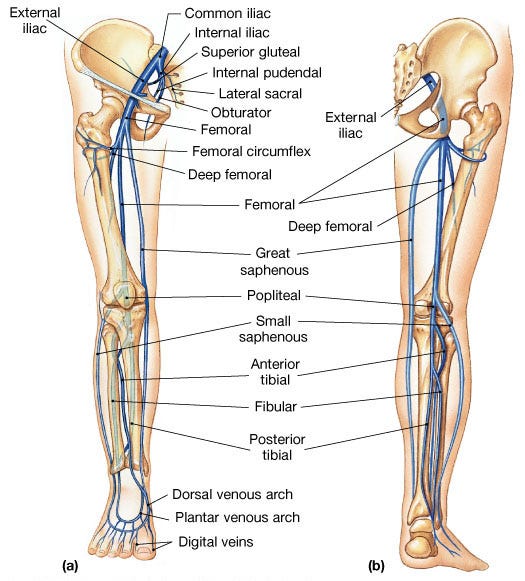

Hansma et al, who believe ‘chicken fat’ clots to be agonal thrombi, state that the latter are ‘often’ in the right side of the heart, and may also extend ‘significantly’ into the pulmonary vasculature (as far as the quaternary branches in one case shown in their Figure 2), ‘although’ (implying I think that this is less common) they may also be seen in the systemic circulation (that is, the rest of the vasculature):

But the thrombus shown in Figure 2 looks too dark to me to be ‘chicken fat’ clot:

With regard to chicken fat clot in particular, the same authors seem to allow for occurrence in the heart and aorta only.

although the caption to the accompanying figure:

indicates that in this case the ‘chicken fat’ clot extended one branch further, into the common iliac arteries:

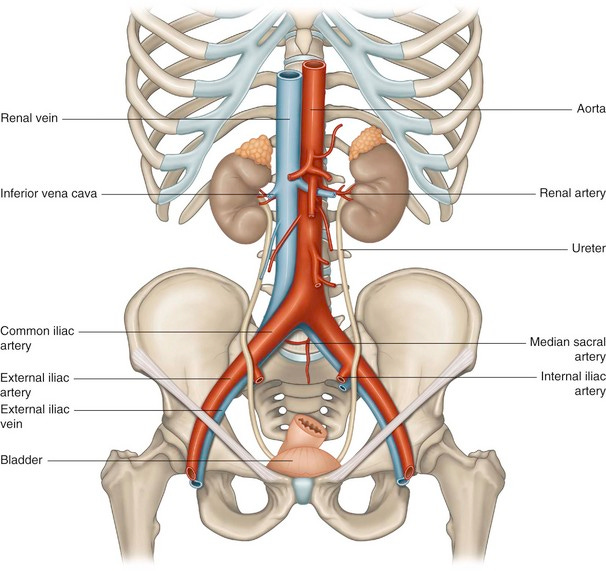

Contrast this with the long lengths of material that the embalmers have pulled out from the veins of the leg from an incision in the external iliac vein (from where the returning blood in a living person flows upward into the common iliac vein):

Is there any description in the literature of post-mortem clot extending the length of the lower limbs?

Jackowski et al (p. 239) highlight a dimensional consideration. They point out that the ratio of vessel wall surface area to blood volume is less in large vessels, and suggest that this will lead to a lower local concentration of plasminogen activator, impeding fibrinolysis and thus promoting clotting:

If post-mortem clot were to form in the leg veins of a body lying horizontally on its back, would the blood separate into plasma and red blood cells all the way down its length so as to give a continuous pale-coloured upper section of a clot? I have found no reference in the literature to ‘chicken fat’ clot being found in leg veins.

B) No evidence

Dr Burnett claims that the embalmers are not experts in blood clotting, and then that they have brought forward ‘not a single shred of evidence’ to support their case. Presumably his argument is that their professional observations and opinions can be completely discounted on the basis that they are not ‘experts’ in their own field, in which blood clotting plays a prominent part.

As an internal medicine physician, Dr Burnett sees living patients and tries, among other things to keep them alive. If, sadly, they pass away, he may have to examine them to confirm that they have died, and state the cause of death where known, but his medical responsibilities I think end there. He does not conduct autopsies on the deceased, a task confined to pathologists and coroners.

Embalmers make one or more incisions in arteries to inject embalming fluid into the vascular system, and one or more incisions in veins to drain blood and other fluids out of it. They aim to distribute the embalming chemicals to the tissues of the whole body. Blood clots can impede the throughput from injection point(s) to drainage point(s), and they can also hinder full distribution to the whole body. They are thus of central concern to embalmers. The leading embalming textbook ‘Embalming: History, Theory and Practice’, in its 5th edition by Robert G. Mayer (2012), has discussion variously of blood clots, blood coagulation, blood agglutination (clumping of red blood cells), and blood viscosity in (and the list is not exhaustive) Chapter 5, ‘Death - Agonal and postmortem changes’, Chapter 6, ‘Embalming chemicals’, Chapter 9, ‘Embalming vessel sites and selections’, Chapter 10, ‘Embalming analysis’, Chapter 12, ‘Injection and drainage techniques’, and Chapter 22, ‘Vascular considerations’. (I have collated some of the relevant passages here.)

Richard Hirschman said in a December interview that he embalmed over 600 bodies in 2021, and that he had been embalming for 21 years. Thus he may have embalmed of the order of 10,000 bodies.

Venous coagula, whether post-mortem or ante-mortem generally emerge in the drainage, as Mayer explains (p. 248):

so embalmers see them very often. If this textbook may be taken as a guide, they study blood clots extensively as part of their training. It describes ‘chicken fat’ clot as a clear jelly-like layer of fibrin on the top of a post-mortem clot (p. 248):

Embalmers are thus extremely familiar with blood clots, both ante-mortem and post-mortem, in both theory and practice. They may make choices about the type and amount of anticoagulants to include in the embalming fluid (Mayer Chapter 6); a likelihood of the presence of clots may affect (Mayer Chapter 9, pp. 179-180) the choice of injection and drainage site(s):

Use of the right internal jugular vein for drainage gives access to the right atrium of the heart via the right brachiocephalic vein and the superior vena cava allowing removal of clotted material from that chamber (Mayer p. 185):

Blood often congeals in the right atrium after death. The embalmer with access from the right internal jugular vein may use an angular spring forceps or other instrument to fragment this coagulation (Mayer Chapter 12, p. 250):

Embalmers are thus used to breaking up clots and are familiar with their consistency. They are in an extremely good position to know if a new type of intravascular material is presenting itself that is different to normal clots. Their statements are based on knowledge and good evidence. They do not necessarily know and understand the science of blood clots, but nor do they need to do so in order to give evidence that this material looks and handles differently to what they have been used to.

Dr Burnett is wrong to say that the embalmers have not provided evidence. They certainly have done so, in the form of observations and opinions of professional people in an extremely good position to make and form them. He has failed even to engage with the primary observation they are making about the material’s strength and toughness. They have also provided video of long lengths of it being extracted from a single incision, bearing witness to at least a degree of strength. And they have provided many photographs, showing the form it takes out, and attesting to its colour and the size of individual pieces of it.

Conclusion

Dr Burnett’s attempt to show that there is no reason to think that the material being found by the embalmers is anything other than normal post-mortem clot falls at the first hurdle. His method is to demonstrate a commonality of characteristics. But his claim that the embalmers describe the material they are finding as gelatinous is unfounded. On the contrary they describe it as ‘strong’ and ‘tough’, which is quite the opposite of jelly-like.

His use of a slide he found on Twitter as his basis for comparison of visual appearance led him, presumably inadvertently, to compare the embalmers’ material with canine ‘chicken fat’ post-mortem clot. This canine clot is whitish in colour, whereas human ‘chicken fat’ clot is shown and described in the literature as yellowish in colour. The reason for the difference in colour may be an absence of bilirubin in canine plasma. If Dr Burnett had compared the embalmers’ material with human ‘chicken fat’ clot, the difference in colour would I think have been clear.

Dr Burnett does not seem to have investigated and compared the patterns of occurrence of the embalmers’ material with human ‘chicken fat’ clot. Post-mortem clot does not always form at all, and when it does, it may coagulate before the red blood cells have separated sufficiently from the plasma by gravitational sedimentation for the resulting clot material to cease being predominantly red in colour. In animals, it is said to occur only ‘occasionally’. How common is it in humans? Hirschman reported (37:13) finding white fibrous clots in 37 out of 57, that is about 65% of the bodies he embalmed in January 2022. Is it plausible, just looking at this criterion in isolation, that such a high proportion had ‘chicken fat’ post-mortem clotting?

I have so far found descriptions of ‘chicken fat’ clot only in the heart and major vessels. But the embalmers’ material has been found extending down the veins of the leg.

Embalmers constantly have to deal with both ante-mortem and post-mortem clotting as they endeavour to distribute embalming fluid to the tissue of the whole body, and drain excess fluids. They are extremely well positioned to make observations about intravascular obstructing material, and have sufficient training and education to form reasoned judgements about they are seeing. Dr Burnett has not succeeded in making a sound case that all the embalmers are seeing is normal ‘chicken fat’ post-mortem clot.

Andrew Chapman

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, they have none at all:

The best rebuttal i have ever seen. congratulations and Thank you Sir.