Rejoinder to Dr Burnett re post-mortem clot

He only weakens his own case

Steve Kirsch tweeting a link to my last post

seemed to stimulate the first response from Dr Burnett to my criticism of his short video, in which he had effectively argued that the material being found by the embalmers was nothing but normal ‘chicken fat’ post-mortem clot. To recap, his argument in brief was that:

A) the embalmers’ description of their material in ‘Died Suddenly’ corresponds to the description of post-mortem clots in Judy Melinek MD’s slide in two respects, namely, that each are described as ‘gelatinous’ and as ‘rubbery’;

B) the visual appearance of each was similar;

C) embalmers are ‘not experts in blood clotting’, so that their opinion that their material is novel is worthless (‘not a single shred of evidence’).

In reply, I:

A) demonstrated that the embalmers did not describe their material as ‘gelatinous’ in Died Suddenly, but rather as ‘strong’ and ‘tough’;

B) showed that the image he showed of post-mortem clot was in fact taken from the heart of a dog, invalidating the comparison;

C) argued that embalmers have a great deal of knowledge and experience of blood clotting, so that their observations and judgements should be given considerable weight.

Dr Burnett has not defended his claim that the embalmers described their material as ‘gelatinous’; and he has admitted that he neglected to check the source of the image:

but denies that this invalidates his claims:

With respect, it certainly does invalidate his visual comparison, since his claim is that the embalmers’ material is human post-mortem clot, not canine clot. And this visual comparison occupied a prominent place in his short presentation. He should withdraw his video and, if he sees fit to revise and reissue it, use an image of human clot for comparison. At the same time he should correct his error about how the embalmers describe their material.

Dr Burnett’s main response to my article was a seven part mini-thread, with five numbered points sandwiched between an opener and a closer; it may conveniently be taken tweet by tweet. Remarkably, he begins by linking to an article by embalmer Benjamin Schmidt, that is, to someone who in his view is ‘not an expert in blood clotting’; the article, he says, ‘thoroughly debunks’ the claims made in Died Suddenly:

Schmidt expresses his opinion about various pieces of the whitish material shown in Died Suddenly, claiming variously that they are ‘consistent with a currant jelly clot or maybe a chicken fat clot’; ‘clearly a mixture of chicken fat clots and sludge’; and of one ‘monster clot’ that it ‘could be a chicken fat clot’ but then again ‘could also be a white fibrin clot’. He offers no reasoning nor any support from the literature for any of these claims. If as an embalmer with no medical training he is not an expert in blood clotting, as Dr Burnett had claimed in his video, then why should his opinions carry weight, and why should they override the opinions of embalmers far more experienced than Schmidt is? Schmidt graduated from Worsham College of Mortuary Science in 2011. Wallace Hooker MBIE, to take one example of the embalmers who believe the material is new, is said to have graduated from the same college in 1994, and to be currently serving on its Advisory Board.1 He is also a Chief Deputy Coroner. How can Schmidt’s opinion, given on the basis of photographs and videos only, without physical examination of the material, ‘debunk’ Hooker’s, who has apparently seen it for himself?

Why would Dr Burnett turn to an embalmer for support of his position, if in his opinion they lack expertise in blood clotting? Perhaps the reason is that he could find no-one, among those he would consider expert, who shares his certainty that these are post-mortem clots. Anatomical pathologist Irene Sansano has suggested that they may be pre-mortem thromboembolisms; but Nikolaus Klupp, an Associate Professor of Forensic Medicine, thinks they look ‘more like’ post-mortem clots. He describes them as ‘scientifically interesting’:

If they were normal post-mortem clots, what would be scientifically interesting about them? The next step, he proposes, should be an histological examination, and with that we may wholeheartedly agree.

Forensic pathologist Judy Melinek did at first say that Dr Burnett is correct:

but after I had asked her how she could know without examining a sample, and posted a link to my first article which summarises what the embalmers are seeing, she retreated to saying that she would have to examine a sample before giving her opinion:

The only other pathologist to have given an opinion, to my knowledge, is Ryan Cole MD, who has examined them, and sharply differentiates (46:12) them from post-mortem clots:

Post-mortem clots tend to be like a thick red jelly you can squeeze them you can roll them around just break them apart; that's the uniqueness of it, these are like rubber bands...

Surgical oncologist David Gorski MD has said that to him ‘most of’ the clots shown ‘look like postmortem clots’:

presumably implying that some do not. But earlier in the same article he said that he had been ‘pretty sure’ that ‘the clots’ shown in Died Suddenly ‘were postmortem clots’, implying that they all looked post mortem to him. But he lacked the ‘expertise’ to be sure:

He then recruited ‘experienced and expert’ embalmer Benjamin Schmidt to review the sections of Died Suddenly that feature the embalmers’ material, in order to educate not only Dr Gorski’s web-site readers but also himself:

which seems to support the case I made in my last article that in some respects (though by no means all), embalmers may be in as good a position to give an opinion about intravascular material found in cadavers as are medical doctors outside a relevant specialty.

Dr Burnett continues with some criticisms of my article. The first is preposterous.

1) Did I say that ‘chicken fat’ clot occurs only in animals?

He claims that I somehow communicated that ‘chicken fat’ clots occur only in animals, and highlighted a sentence in ‘The Aetiology of Deep Venous Thrombolism’ (Springer, 2008) by P.C. Malone and P.S. Agutter, where the authors quote from Robbins’ well-known human pathology textbook (1962 edition) on ‘chicken fat’ clots, to show that they do occur in humans. But I had myself quoted directly the parallel passage in the 7th (2004) edition of Robbins in my article:

as well as the relevant passage in Knight’s (human) ‘Forensic Pathology’, and comments by Dr Senanayake about the plasma (‘chicken fat’) part of (human) post-mortem clot. I also shared comments that embalmer Richard Hirschman made about ‘chicken fat’ clot, and included a photo that he sent me of such clot. He embalms humans not animals.

The only reason I wrote about animal ‘chicken fat’ clot at all was that Dr Burnett had (inadvertently) used an image of canine clot in his video. Having found the source of the image in a veterinary textbook, I quoted a couple of sections of interest in the accompanying text before ‘returning to human post-mortem clotting’:

with discussion of papers by Jackowski et al, Uekita et al, and Hansma et al, all with regard to human ‘chicken fat’ clot. I even included two diagrams of the human venous and arterial systems to give context for a photo in Hansma et al of ‘chicken fat’ clot. How can Dr Burnett have missed all this, if he read my article before responding to it?

2) Did Malone and Agutter describe some post-mortem clots as entirely white?

Dr Burnett continues:

The quoted section:

is also from Malone and Agutter’s book, of which substantial sections, including much of Chapter 13, are available online. They outlined the thesis of their book in an open access article in QJM in 2006. Burnett’s extract looks like it may be from the Introduction. ‘VCHH’ stands for the Valve Cusp Hypoxia Hypothesis that the authors are advancing (that thrombi form (p. 141) when the inner endothelium of the venous valve cusp leaflets suffers injury due to lack of oxygen).

Dr Burnett is mistaken, Malone and Agutter do not ‘describe some post-mortem clots as entirely white’. In his short video, Burnett defined post-mortem clots as clots that form after death:

Malone and Agutter state repeatedly, diverging from the view of Robbins and others, that they do not believe that any clots form in blood vessels after death, for example on page 226:

On page 228 they declare that all coagulation and all thrombosis within blood vessels ceases after death due to the lack of oxygen:

and on the same page they explicitly distinguish between when coagula are found and when they are formed. They do refer to post-mortem coagula but only in the sense that they were found in a post-mortem examination. They state that all such coagula were formed before death. They are therefore pre-mortem clots in Dr Burnett’s terminology:

Malone and Agutter’s statement concerned post-mortem blood, which is blood as it is found at post-mortem examination. Clots found in it may in principle have been formed either pre mortem or post mortem. Thus the meaning of ‘pre-mortem’ as an adjectival modifier of ‘blood’ is different to its meaning as a modifier of ‘clots’. These particular authors hold what is probably a minority view that all clots (or all clots in blood vessels) are formed pre mortem.

It may be added that Malone and Agutter generally prefer (p. 583) to maintain the historic terminology which distinguishes between in vivo thrombi and in vitro clots:

Thus W.H. Welch, for example, had defined a thrombus as a solid mass or plug formed in the living heart or vessels from constituents of the blood:2

So when Malone and Agutter, in the extract shown by Dr Burnett, say that post-mortem blood may “be entirely ‘white’ thrombi” (whatever they may mean by ‘entirely’), they are referring to pre-mortem clots, in Dr Burnett’s terminology.

In passing, with regard to our authors putting ‘white’ in inverted commas in Dr Burnett's extract, we may observe further that the term ‘white thrombi’, as it has been used historically to refer to thrombi formed from circulating blood rather than from stagnating blood, can encompass also ‘mixed thrombi’:3

and that this broader group formed from circulating blood may in fact be predominantly red in colour through admixture with red blood cells:4

To return to the main point, and to conclude, Dr Burnett’s short extract has nothing to do with what he calls post-mortem clots, at least in the view of his authors, who believe them not to exist. He is thus appealing, in support of his thesis that the embalmers’ material is post mortem, to authors who would certainly say that it is not post mortem!

3) Another statement about post-mortem blood

Dr Burnett adds another extract from Malone and Agutter, again about the presence of coagula in ‘post-mortem’ blood:

Again, the authors’ statement about coagula found in post-mortem blood lends no support to Burnett’s thesis that the embalmers’ material is post-mortem clotting, which is to say clotting that is formed after death. As we saw above, the authors’ answer to the question of this section heading, ‘Can Blood Coagulate in a Cadaver?’, is that it cannot do so.

By way of further explanation, their view is that the type of clotting normally identified as ‘post-mortem’ is in fact agonal, which is to say that it is formed during the dying process.

If Burnett were persuaded by their arguments, he could put forward a new thesis, that the embalmers’ material is normal agonal thrombus, and cannot therefore be a cause of their death. But this would be a different debate, since the mode of formation proposed by Malone and Agutter (and their predecessors) for ‘white’ agonal thrombi, is different from the mode of formation of ‘white’ post-mortem clots in what is currently the standard view as explained by Robbins and others (see discussion of point 5 below, and my Appendix).

As it turns out, Dr Burnett disagrees with the authors he is citing in support of his case, and has recently reiterated his belief that clots can form post-mortem:

He gives no reference for the factors he lists in this tweet that can in his view cause blood to coagulate post-mortem. I only note that they are all factors given in the article by embalmer Benjamin Schmidt that Burnett linked to in the first tweet of his thread. If he is relying on an embalmer for his knowledge of post-mortem clotting, then he is further weakening his argument that embalmers are not experts in blood clotting.

4) Is Steve Kirsch claiming that the embalmers’ material is post-mortem?

With regard to the next tweet, I can only think that Dr Burnett has somehow imported the meaning of ‘post-mortem’ as it is employed as an adjectival modifier of ‘blood’, that is, ‘found post-mortem’ - into its use as a modifier of ‘clots’, that is, ‘formed post-mortem’. He has somehow begun to think that Steve Kirsch is claiming the embalmers’ material is post mortem, that is, formed post mortem according to Burnett’s own definition:

The embalmers frequently explain why they believe the material they are finding is not normal post-mortem clotting and to my knowledge they have never suggested that it is formed after death, even in some abnormal way. They have sometimes commented that in their personal (not professional) opinion, they think that the material may well have caused the person’s death, implying that they believe it to be pre mortem. Likewise I doubt that Steve Kirsch has ever suggested that this material is formed after death. In the nature of their profession, the embalmers are of course finding it after death.

With regard to Malone and Agutter’s observation that if blood is liquid post mortem then death was acute and sudden, I commented in my last article on the related reverse proposition, that if death is acute, then the blood is (normally) liquid:

Funeral Director John O’Looney has described a case of a young man who died suddenly, had a post-mortem examination, and whose arteries were then found by O’Looney’s embalmer to contain a great deal of the strong whitish material that other embalmers have been describing. Depending to some extent on the nature of the sudden death, his blood would probably I think be expected (even according to the standard theory) not to coagulate after death. The intravascular material found is therefore, for this reason alone, unlikely to have been post-mortem clot.

Insofar as the embalmers’ material may be found in the bodies of people who have died acutely or suddenly, this association between such death and liquid blood would tend to weaken Dr Burnett’s case that it is post-mortem clotting.

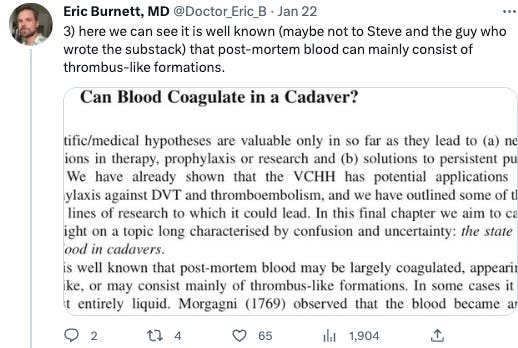

5) White clots and ‘long streamers’

In the extract from Malone and Agutter attached to Dr Burnett’s next tweet, they are explaining the views of Ludwig Aschoff, who was a proponent of the other school of thought about post-mortem clotting, with which they are in disagreement:

Again, the fact that these various coagulation formats are found at post-mortem does not in itself signify that these are ‘post-mortem blood clots’. However, the statement that body position after death ‘determines or significantly influences’ their ‘position and stratification’ seems suggestive of at least part of their formation occurring after death.

The paragraph as a whole reads:

Aschoff was putting forward the view, which is now the standard explanation (Robbins, Knight, al.) of ‘chicken fat’ clot, that blood can separate after death by gravitational sedimentation, resulting in a yellowish ‘chicken fat’ portion and a dark red portion beneath it, ‘as in a beaker’ as he puts it. His mention of ‘buffy coat’ suggests that he may have had in mind the separation that can take place into not only two but three layers, with a thin intermediate layer replete in white blood cells and platelets, still referred to as ‘buffy coat’ in modern textbooks (p. 647):

I have very roughly (machine-) translated a few pages of the 1916 paper by Aschoff that Dr Burnett is referring to, ‘Über das Leichenherz und das Leichenblut’ (‘Regarding the heart and blood of cadavers’)5, and my impression is that Aschoff's central purpose is to dispute the contention made by Hugo Ribbert, one of the pathologists of the opposing school of thought, that certain types of clot found especially in the heart are agonal rather than post-mortem. On page 4, for example, Aschoff is I think saying that liquid blood was found in bodies dissected immediately after death, where clot would be expected to be found at a normally timed post-mortem examination, the implication being that post-mortem clot had not had time to form, with little or no clot being formed in the agonal period. Ribbert’s agonal hypothesis was thus found to be untenable ('unhaltbar'):

The coagulation formats listed by Malone and Agutter, in their presentation of Aschoff’s view, are buffy coat, ‘cruor’, ‘hard thrombi’, yellow clot, white clot, and long streamers. Dr Burnett makes particular note of the last two, presumably because they could be compatible with the embalmers’ description of their material, it being whitish, and sometimes in very long lengths. For sake of argument, I am willing to assume that they were all formed post mortem in Aschoff’s view, even if I am a little puzzled by the inclusion of ‘hard thrombi’. Aschoff seems to have distinguished, according to the terminology then current, between the formation of ‘thrombi’ in living people and post-mortem ‘clots’, as can be seen in his 1924 lecture on thrombosis (p. 260-1):

But possibly ‘hard thrombi’ was placed in inverted commas because it was a term for a certain type of post-mortem clots that is similar to a hard type of in vivo thrombi?

I have done a quick search by eye in Aschoff (1916) for the words ‘gelb’ (yellow) and ‘weiss’ (white) but found no reference to ‘yellow’ or ‘white’ clots. There are repeated references to Cruor and to ‘Speckhaut’. ‘Cruor’ is also used in English, and means either ‘coagulated blood’ in general, or ‘that part of the blood which forms the blood’:

Hansma et al, probably with reference to usage in ‘historic authors’ identify ‘cruor’ with ‘black currant jelly’ clots;

which are found post mortem in veins and sometimes arteries:

‘Speck’ means ‘bacon fat’6, and 'speckhaut' is variously translated by Google Translate as 'bacon fat', 'blubber' or 'buffy coat'. In these notes on an autopsy case from (p. 5) Aschoff (1916):

machine translated (with one edit) as follows:

it seems to me that ‘cruor’ is used both of the dark red part of the clot, where separation has taken place, and of dark red clot where there has been little or no separation. Hansma et al also use ‘cruor’ of the dark red part of separated clot in the caption to their Fig. 5 (shown in my last article):

Since ‘Speckhaut’ can be translated ‘bacon fat’ or ‘blubber’ instead of ‘buffy coat’, then I think that it is probably the same as what in English we call ‘chicken fat’ clot, which is usually described as yellow and gelatinous. If that is correct then there appears to be no substantive difference between Aschoff’s account, and the modern standard account of Robbins, Knight and others. I have not been able to identify any ‘white’ post-mortem clot in Aschoff (1916) which bears more resemblance to the embalmers’ material as they describe it than does the human ‘chicken fat’ clot which was the subject of my last article.

Long streamers

Dr Burnett also draws attention to the ‘long streamers’, another of the ‘coagulation formats’ which Aschoff is said to have found at post-mortem. I have not so far found any reference to them in Aschoff’s 1916 paper, and there is no further mention either of them or of yellow and white clot in Malone and Agutter’s book which could contain an explanation of what they are:

I asked Dr Burnett about them on Twitter, but did not receive a reply. ‘Long streamer’ fibrils are described in ‘On the Origin of Reticulin Fibrils’ in the American Journal of Pathology (1927):

but these are not formed of fibrin (p. 409), and seem (so far as I can tell) to be connected with a later stage of the healing of wounds than the initial clot formation. They do however, in my mind at least, raise the possibility that Aschoff’s ‘long streamers’ are of a much smaller scale than the long pieces of material being extracted by the embalmers.

In conclusion, I have not been able to find any description in Aschoff of material that bears more resemblance to the embalmers’ material than does normal ‘chicken fat’ clot. If Dr Burnett is relying on Aschoff for the existence of other forms of post-mortem clot, then it behoves him to show us the relevant passage and the description of ‘white clot’ or ‘long streamers’. He has added nothing to his argument unless he can do so. If anything, his resort to a reference to a description of an article from 1916, tends to suggest that there is nothing in more recent literature that might support his argument, so that if they do exist they are probably rare. Thus he only weakens his argument again.

Conclusions

Dr Burnett has not succeeded in bolstering his already very shaky case that the embalmers’ material is normal post-mortem clotting, but rather he has only weakened it.

With his assertion that embalmer Benjamin Schmidt has ‘debunked’ the claims made by the embalmers in Died Suddenly, Dr Burnett has torn down what remained of the third pillar of his own case, namely that the opinions of embalmers can be safely ignored since they supposedly lack expertise in blood clotting.

He is mistaken in his assertion (point 1) that I communicated somehow that ‘chicken fat’ clot occurs only in animals.

He is mistaken in his claim (point 2) that Malone and Agutter describe some post-mortem clots as white. These authors, to whom he appeals five times, do not even believe that such clots exist. They are referring to clots found in blood examined post mortem. In their view, all such clots are formed pre mortem, that is, are pre-mortem clots.

Likewise, his statement (point 3) that post-mortem blood (as it is found post mortem) can consist mainly of thrombus-like formations has no bearing on the prevalence of post-mortem clots (which by definition are formed post mortem). As already stated, the authors he appeals to do not believe that post-mortem clots exist at all.

He is mistaken in supposing (point 4) that Steve Kirsch believes the embalmers’ material to be post mortem. On the contrary, every indication is that Kirsch believes it to be formed pre mortem. The association Dr Burnett draws attention to, between sudden death and the blood being found to be liquid post mortem, can provide evidence that the embalmers’ material is not post mortem, in so far as there may be cases where they have found it in the bodies of people who have died suddenly or acutely.

He has drawn attention (point 5) to evidence that one hundred years ago a German pathologist was (according to Malone and Agutter) identifying not only cruor and ‘yellow clots’ (which may provisionally be identified as ‘chicken fat’ clots) but also ‘white clots’ and ‘long streamers’, and that he probably (going by the role he assigned to body position after death) believed these to be formed post mortem. But I have not so far been able to find any reference to these in the 1916 paper that Dr Burnett references. If he can provide a description of these ‘white clots’ and ‘long streamers’ then a comparison could be made with the embalmers’ material. Resort to a century old paper seems to suggest an absence of any description in more recent literature of such coagulation formats in. Again, the authors he draws this information from do not themselves agree with Aschoff that blood can coagulate at all post mortem, let alone form the strong material that the embalmers are describing.

In the final tweet of his mini-thread response to Steve Kirsch sharing a link to my article criticising his video, Dr Burnett protests that the matter is now ‘old’ and should be dropped:

What is he suggesting? That all of us who are very alarmed by the embalmers’ reports should now relax, on the basis that Dr Burnett has assured us that the material they are finding is just normal post-mortem clot? But Dr Burnett is the only medical professional I am aware of (Dr Gorski being an exception in one of his statements but not the other) who has affirmed definitely that it is indeed post-mortem clot. And he is not a specialist. Of the pathologists, Dr Sansano is inclined to believe that these are pre-mortem thromboembolisms, while Dr Cole, who has examined the material, believes it to be novel. Of those with a forensic specialty, both Dr Klupp and Dr Melinek seem inclined to think that it may be post mortem but, like Dr Sansano, neither is willing to give a definite opinion without examining it for themselves, Dr Klupp mentioning the particular need for histological examination.

Dr Burnett’s response has, in various ways, confirmed the validity of all three of my central criticisms of his video. First, by not defending his previous claim that the embalmers described the material as ‘gelatinous’, he has effectively confirmed that the embalmers’ description does not match the descriptions of post-mortem clot in the literature, particularly with regard to consistency and strength. Second, he has not so far produced an image of human post-mortem clot that is at all similar to the images being provided by the embalmers. Third, he seems to have accepted that embalmers do have considerable knowledge and experience of blood clots as they present themselves in dead bodies, so that their opinion should be given considerable weight. He has given no reason why the opinion of one particular embalmer should be preferred before others.

The matter may indeed be ‘old’ in the sense that it is more than a year now since Richard Hirschman first raised his concerns publicly. But it is also right up to date, since he and others are still finding the material which they believe is new, so that peoples’ lives may continue to be in danger from what is as yet an undetermined cause. If the embalmers are right, then this is a matter of extreme concern. This is not at all the time to drop the matter, but to redouble efforts to have the matter fully investigated by competent bodies.

I appreciate Dr Burnett’s contributions in the public space, and pray that he will realise that our debate can only be settled through such an investigation. There is no reason why people currently on opposite sides of the argument could not agree on the need for this. There must be a full report, with full transparency of data including microscopy images, and detailing of the investigative methods, the results obtained, and the reasoning employed to reach whatever conclusions they may come to.

Andrew Chapman

APPENDIX: parallel historical difference of view on thrombus formation

There was a difference in view about the formation of thrombi that paralleled the difference of opinion about whether coagulation occurred post mortem, and sheds light on its origins.

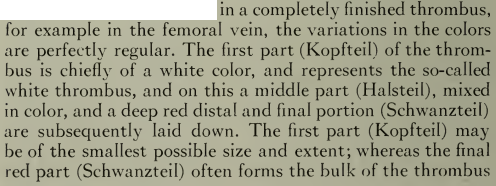

According to Aschoff’s account (pp 254-5), a ‘completely finished thrombus’, in a femoral vein for example, has three parts, a white head (Kopf-), a mixed neck (Hals-), and a red tail (Schwanz-), which is often the largest:

The white thrombus is formed first, drawing platelets and then leukocytes from the circulating blood. Once it has more or less completely obstructed the blood vessel (p. 255):

then (in Aschoff’s view) the whole blood column becomes stationary and coagulates very rapidly (p. 260):

This coagulated column of blood is red, as one would expect, and it is this red thrombus that is compared (pp. 260-1) to post-mortem clot (as shown also above):

This comparison of a coagulum formed from a stationary column of blood to post-mortem blood is made again a few pages later (p. 268):

This makes sense, since the blood in the femoral vein of a cadaver is also stationary, if more completely, since not only is the circulation at a standstill, but the body also. If such blood does coagulate after death in its vessel, then Aschoff’s comparison suggests that it will be red and ‘spongy’, a description consistent I think with ‘gelatinous’, the epithet commonly employed in modern descriptions of post-mortem clot.

An 1891 textbook account of blood clotting begins helpfully (p. 15) with its gross physical behaviour out of the body. If fresh blood is shed and collected in a container, it will first become viscous and then coagulate, forming a perfect ‘jelly’, which can be gently shaken out as a mould of the interior of the container:

In humans, blood becomes viscous in two to three minutes, and gelatinous in five to ten minutes (p. 15). After another few minutes, liquid serum begins to emerge from the jelly, this process continuing until a more solid ‘clot’ is left floating on the liquid serum:

the whole process taking one to several hours. The blood normally becomes viscous before there is any appreciable gravitational sedimentation of the red blood cells, so that the jelly is homogenous.

If the blood does separate before it becomes viscous, in humans because of ‘abnormal conditions of the body’, then all three layers, plasma, buffy coat, and red, will clot, as Professor Foster explains (p. 16) with regard to horse blood, which does separate before becoming viscous, especially at low temperatures:

The gross behaviour of blood outside the body is uncontested, and important to understand as background. As Malone and Agutter say (p. 226), we should keep in mind ‘that “normal” fresh blood shed into a receptacle coagulates rapidly en masse’:

The situation is different with blood in its own vein or artery. Aschoff admitted (p. 268) that Baumgarten had shown that stationary blood in a doubly ligated blood vessel (tied in two places) remained liquid, but held that blood made stationary by a thrombus behaved differently and does coagulate:

Malone and Agutter disagree (p. 228), maintaining that even the tail part of the thrombus forms in blood that is moving, if only slowly:

This difference of opinion parallels the difference of opinion about the coagulation of the stationary blood of cadavers. Aschoff believed that it does coagulate, Malone and Agutter, following Ribbert, that it does not.

But what about the yellowish ‘chicken fat’ clot that was often found in the heart and major vessels of cadavers? Aschoff believed that its colour resulted from a gravitational separation of the plasma from the red blood cells after death and before coagulation. This is why he believed, as stated in the extract shared by Dr Burnett, that the position of the dead body determined or significantly influenced the position and/or stratification of the coagula.

Ribbert, as quoted by Malone and Agutter, countered (p. 223) that in some cadavers there was too much white coagula, and too much buffy coat for it to have separated out from the blood after death:

I am not sure whether ‘white coagula’ and ‘buffy coat’ are referring to the same material, the first term representing Ribbert’s understanding of its formation from circulating blood, and the second representing the other school of thought where it is understood as a gravitational layer. On the other hand, ‘buffy coat’ and ‘white clots’ are listed separately in Malone and Agutter’s account of Aschoff’s views. I do not yet understand how there could be four layers: yellow, white, buffy coat, and red, in Aschoff’s gravitational separation model.

According to Ribbert, a very high concentration of leukocytes in a clot or thrombus could only come about through their sequestration from circulating blood (p. 223):

Ribbert also argued (p. 223) that if blood coagulated after death, then it would all do so, as it does in a vessel outside the body. But cadavers in fact contained fluid blood alongside the solid masses:

He describes (p. 223) a white clot in the heart that continued into the pulmonary artery and aorta and arterial branches. The only way to explain such a clot, he argued, was by the sequestration of material from circulating blood:

Further quotations from Ribbert make clear that it is specifically the addition of leukocytes from the circulating blood that gives rise to the ‘white clot’. In some thrombi, he had found so many leukocytes that it seemed to him as if there could be none at all remaining in the circulating blood:

As the patient is dying, white blood cells swarm to particular locations, notably both veinous and cardiac valves, to try to repair damage:

A combination of whitish and dark red clot found in the heart after death would thus be explained as a result of a concentration of white blood cells in the heart before death, rather than as gravitational sedimentation of red blood cells after death.

Perhaps there is truth in both schools of thought, with buffy coat/white clots gaining their colour from white blood cells in the agonal period, and yellow clots being plasma clots, as Knight calls them (p. 341), arising from gravitational sedimentation after death?

Mr Hooker has confirmed in a personal communication that these biographical details are up to date.

Welch, W.H. (1899) ‘Thrombosis,’ in Allbutt, C. (ed.), A System of Medicine, vol. 6; Macmillan, London, p. 155.

Welch, op. cit., p. 155.

Welch, op. cit., pp. 155-6.

Aschoff, L. (1916) ‘Regarding the heart and blood of cadavers,’ Beiträge zur Pathologischen Anatomie und zur allgemenein, Vol. 63, 1.

Oxford-Duden German Dictionary, 2nd., Oxford University Press.

TQ for the work you do. indeed, the only possible conclusion should be that more research is needed as well as more transparency, particularly with regards to the possibility of adverse effects from the C19 injection(s). gruesome times these are!