Normal or abnormal?

A refutation of Benjamin Schmidt's article (part 1)

My rejoinder to Dr Burnett prompted a response in the form of another Twitter thread, this time from Dr Jonathan Laxton MD FRCPC, an internal medicine physician and Assistant Professor of Medicine at the University of Manitoba. Like Dr Burnett and Dr Gorski (see my last article), he had recourse to an article by Benjamin Schmidt at ‘Science-Based Medicine’ (where Dr Gorski is the Managing Editor):

Personally, for reasons which will I hope become apparent, I find it surprising that any medical doctor would find Schmidt’s article at all persuasive. But, since these three apparently do, and there are many other people who use it to dismiss the reports coming from the embalmers, it seems necessary to refute it.

In an article published on the same day as Schmidt’s, 5 December 2022, Dr Gorski explained that he had invited him to write a review of those parts of Died Suddenly which featured the intravascular material being found by embalmers in the course of their work:

Schmidt had assured Gorski that this material was in fact the result of nothing other than normal post-mortem clotting:

Although SBM’s editor describes Schmidt as ‘an experienced embalmer’, it seems possible that it was in fact his lack of experience that resulted in his coming to what in my view was a premature judgement. The bio accompanying the article claims only that he was licensed as an embalmer some time after graduating from Worsham College of Mortuary Science in 2011, and that he spent four years in the funeral directing and embalming field:

which is consistent with the information on his LinkedIn page, where he does not describe himself as an embalmer at all:

but does show four years (2011-15) experience as a ‘Funeral Director/Embalmer’ at Laird Funeral Home in Illinois:

He then became an Instructor at his alma mater, Worsham College, in subjects including ‘Embalming Theory and Laboratory’ according to publicity advertising a 2019 training session for the Massachusetts Funeral Directors Association, who also described him as a ‘nationally regarded embalmer and restorative artist’:

With regard to Dr Laxton setting Benjamin Schmidt’s opinion over and against that of practising embalmers Richard Hirschman, Wallace Hooker, Anna Foster, Nicky Rupright King, Chad Whisnant, Cary Watkins and Brenton Faithfull, the most important point is that there is no indication that Schmidt was embalming during the period from early to mid 2021 when the above named describe finding something other than normal clot. It is also clear that he has not seen the material for himself, but is basing his view on the images, video footage and interviews shown in Died Suddenly.

Schmidt’s method, such as it is, seems to be claim greater weight for his own view than that of the embalmers featured in Died Suddenly. These embalmers, Schmidt asserts, are completely unqualified to give an opinion about the material they are encountering in their work:

But if this is the case, why should we place any weight on Schmidt’s opinions? He does not give a reason explicitly, but does in the next sentence bring in the fact that he is now an instructor in embalming at the same college where both he and one of the embalmers interviewed in Died Suddenly had studied:

The embalmer referred to is presumably Wallace Hooker CFSP MBIE, who graduated from Worsham College in 1994, seventeen years before Schmidt, and now serves on its Advisory Board, as well as on the board of the North American Division of the British Institute of Embalmers.

There is no indication that Schmidt has any formal qualifications that the other embalmers lack. He became an instructor but this does not in itself demonstrate competence. He no doubt makes use of textbooks in his classes and, while he gives no specific references for any statements in his article, he does give a general reference to two textbooks:

Of these two, Mayer is more than twenty years more recent, and has 249 ratings on Amazon, compared to just 4 for Strub.

Schmidt makes the absurd accusation against embalmer Richard Hirschman that the latter did not pick up his embalming textbook during his training:

But Hirschman first qualified from mortuary college, and then passed his examinations to be licensed as an embalmer in the same way as Schmidt did, though about a decade earlier. Schmidt very probably makes more use of embalming textbooks than Hirschman has need to now, but the latter is a practising embalmer, while Schmidt has given no indication that he has practised embalming since 2015. Whose judgement is likely to be more reliable I will leave the reader to judge.

A ‘patently false’ claim?

Schmidt discusses a scene in Died Suddenly where Hirschman is shown extracting a long length of material from what he refers to as the ‘iliac’ artery of the deceased. As Schmidt points out, the artery in question is almost certainly more specifically the external iliac, rather than the common iliac. Since the common iliac is not used by embalmers as an injection point for non-autopsied bodies, no ambiguity results here from referring to the external iliac as ‘the iliac’ as a shorthand. Indeed, having pulled Hirschman up on this minor point:

he uses the same shorthand himself twice in the very same paragraph!

According to Schmidt’s description of the scene, Hirschman pulls ‘clots’ out of the [external] iliac artery, and claims that ‘this is not normal’:

Schmidt seems to understand Hirschman as saying that it is not normal to pull clots out of the iliac artery. In fact, Hirschman makes two claims, first that embalmers normally do not see clots in arteries at all:

[0:05] This is the iliac artery, and the clot coming out of the iliac, normally we don't see clots in.. an artery, usually they are in veins..

and second that what he is encountering on this particular occasion is not normal:

[0:30] and I'm probably not going to be able to get it all.. [having pulled out 2-3 ft of material; 0:38] this is not normal..

It is apparent that his comment ‘this is not normal’ is provoked by the fact that more and more of this material is coming out in a single length. While it is being stretched as it is pulled out, it can be seen to be whitish in colour under the blood that covers it (see the short section on the lower strand next to the forceps):

and this also may perhaps have contributed to it apearing abnormal to Hirschman.

When an incision is made in a blood vessel, there are two directions from which material could be pulled out. In this case, given that it is long and thin, it is fairly obvious that it is being pulled out of the leg rather than out of the trunk. In an interview given in January 2022, when Hirschman shared the same footage, he said explicitly (0:35 ff.) that the material came out of the leg.

Has any such thing been seen before 2021, that a single long piece of material should be pulled out of someone’s leg arteries from one incision? Schmidt does not address this question at all.

Instead, he restricts himself to the question of whether it is normal to find a clot of any kind in the external iliac artery. By saying that clots are ‘usually’ in veins, Hirschman has made it clear that clots may on occasion be found in arteries, but less commonly than in veins.

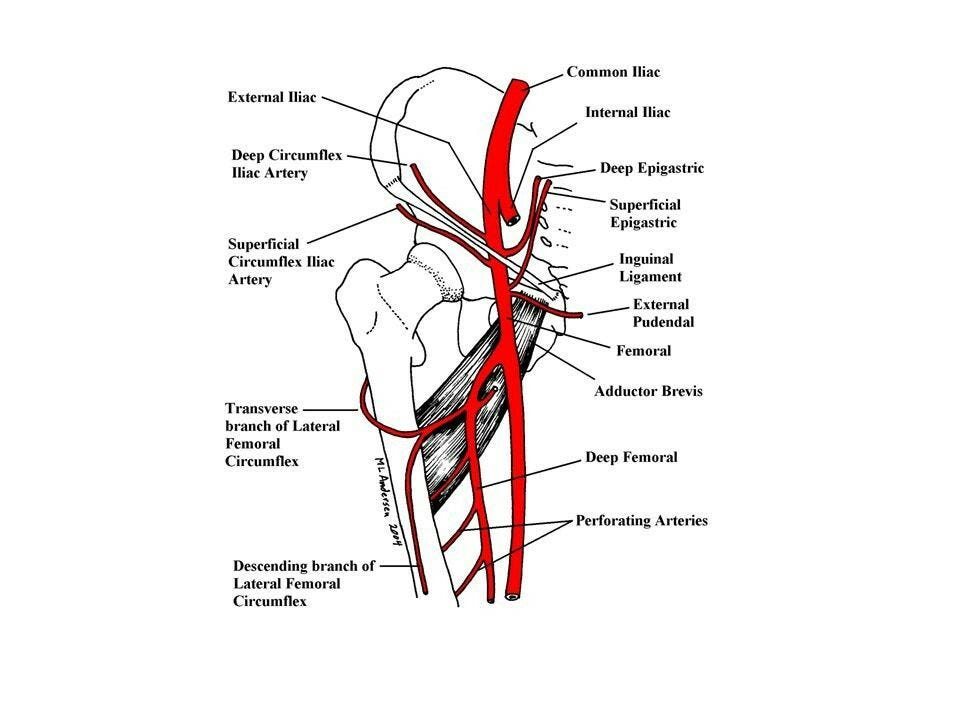

Schmidt points out that the external iliac artery becomes the femoral artery where it ‘crosses’ (passes under) the inguinal ligament towards the leg:

as is also stated in Mayer chapter 8 ‘Anatomical Considerations’ (p. 168):

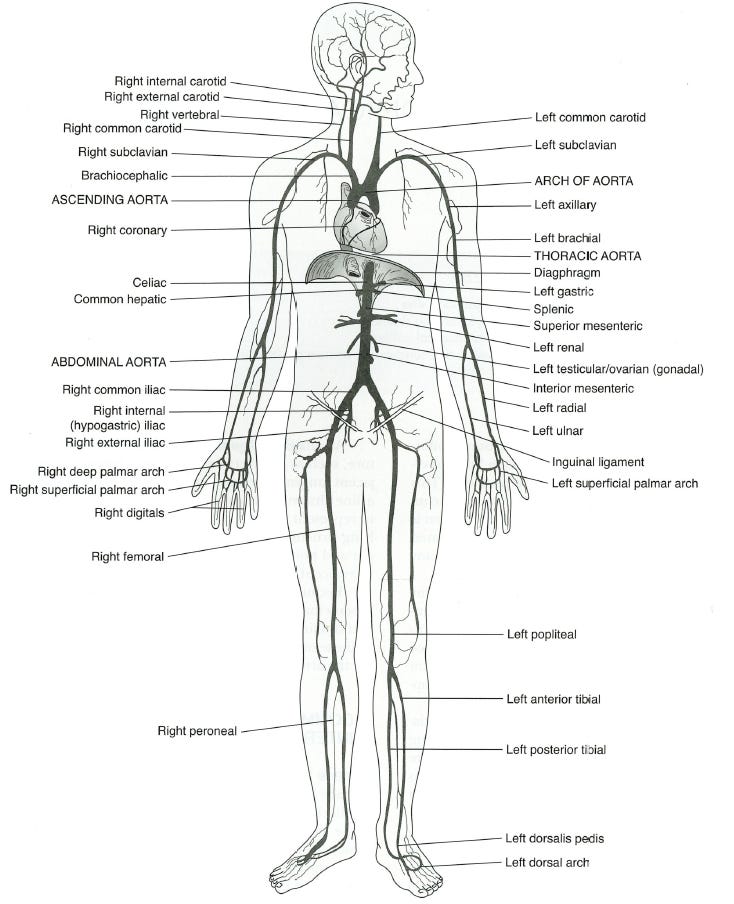

and as can be seen in this diagram:

An injection tube may be inserted in either direction at the point of arterial incision, and two tubes may be inserted at the same point, one in each direction. Mayer points out that an arterial insertion into the femoral artery in the direction of the upper part of the body actually places the tip of the tube into the external iliac artery, so that the term ‘iliofemoral’ may be employed for the use of blood vessels near to the inguinal ligament:

In Chapter 9 ‘Embalming Vessel Sites and Selections’, with regard to considerations about the use of the external iliac for arterial injections, Mayer refers (p. 193) the reader back to his discussion of the use of the femoral artery:

confirming that issues that may arise with injection at the femoral may also arise at the external iliac.

A ‘danger area for clots’

Schmidt continues by saying that this (iliofemoral) area is prone to atheroscelerosis, which ‘slows blood’ and ‘can capture clots’:

Atherosclerosis is a thickening or hardening of an artery due to a build-up of plaque on the inside of it. A resulting stenosis (narrowing) of the artery, while the patient is alive, may reduce the volumetric blood flow.1 Femoral atherosclerosis is a common cause of claudication (leg pain) and critical limb ischaemia (loss of blood flow).2 I have not found any association with thrombosis (pre-mortem clotting), but in any case Schmidt does not say that atherosclerosis causes clots, but rather that it 'captures' clots.

His point, presumably, is that an arterial embolus could lodge in this iliofemoral area because of stenosis, as described in the literature:3

but if it did so, it would be ‘upstream’ of the place of narrowing, that is, on the trunk side, whereas Hirschman extracted his length of material from the leg side of his incision. In any case, Schmidt’s general thesis is that Hirschman is extracting post-mortem clots, not pre-mortem thrombi or thromboemboli, and his opinion regarding this particular case is that the material removed is consistent with ‘currant jelly clot’ or ‘chicken fat clot’:

which he had previously defined as types of post-mortem clot (only his first two categories shown):

Schmidt continues his discussion of the extraction from the external iliac artery, by claiming that Hirschman’s textbook should have taught him that this location is a ‘danger area’ for ‘clots’ and ‘arterial blockages’:

The reference to ‘danger’ is a little odd. Clearly the deceased are no longer in any danger from clots or ‘arterial blockages’. Arterial thrombosis and thromboembolism may certainly be dangerous to the living, but these are topics for medical textbooks not embalming ones. Post-mortem clots may cause problems for the embalmer, but they are hardly a ‘danger’ to him or her.

Let us now see what Hirschman and Schmidt would in fact have learned from their embalming textbooks about the iliofemoral area and clots.

Atherosclerosis and clots in Mayer

In a section on ‘Selecting an artery as an injection point’, Mayer points out (p. 178) that the femoral artery is frequently sclerotic, in contrast to the common carotid which rarely exhibits arteriosclerosis (of which atherosclerosis is a type):

In a section on the ‘Elevation of vessels’ (prior to injecting them), Mayer observes (p. 181) that sclerotic arteries may be still be used if the injection tube can be inserted:

Clearly stenosis (narrowing) resulting from sclerosis will be of concern to embalmers if the lumen (the interior of the artery) is too small for the injection tube.

In a section on ‘Vessels used for arterial embalming’ and sub-section ‘Femoral artery’, Mayer states (p. 189) that the most common reason why this artery cannot be used as an injection point is arteriosclerosis:

He does not associate arteriosclerosis or atherosclerosis in particular with either pre-mortem or post-mortem clotting in any passage I have found.

Post-mortem evacuation of the arteries

Mr Schmidt may recall the ways in which embalmers are able to distinguish between arteries, veins and nerves, which tend to be grouped together (Mayer, 176):

According to the accompanying table (p. 192):

the arteries are ‘generally empty of blood’ after death.

In a section on ‘Drainage’, Mayer explains (pp 247-8) that there is generally a ‘wave contraction’ of the arterial system after death, which forces most arterial blood into the capillaries and veins. After death, an estimated 5% of the blood is found in the arteries, compared to 10% in the veins, and 85% in the capillaries:

In Chapter 22, in a section on ‘Arterial Coagula’, Mayer says (p. 424) that some blood does remain in the arteries, especially in the large aorta:

Arteries derive their very name from the fact that the Greeks found them empty of blood at death and supposed (until corrected by Galen4) that they were air ducts:5

In an older embalming textbook, Professor Carl Barnes stated (p. 127) that post-mortem contraction of the arterial muscles forced all the arterial blood into the capillaries and veins:6

Mayer comments (p. 177) that the femoral arteries are more muscular than the carotids:

which could potentially cause them to empty their blood more fully. If an artery contracts fully, emptying all its blood, then it can of course form no post-mortem clot at that time. The arteries may expand again later, but if the blood in the veins has coagulated, the arteries will be filled with gases. If the blood in the veins has not coagulated, then some blood may return to the arteries, but may be expected to remain fluid, as suggested by the acccount in an a nineteenth century textbook of physiology:7

In which arteries may post-mortem clotting occur?

In the section on ‘Arterial coagula’, quoted above, where it is stated that some blood remains in the arteries, and particularly in the large aorta, Mayer goes on to add (p. 424) that this blood may congeal:

Mayer makes particular mention of the aorta with regard to clotting elsewhere (p. 179):

and again on page 245:

For an hypothetical case study, he posits (p. 180) ‘a clot or coagulum’ present in the abdominal aorta:

Finally, in a section on ‘Restricted Cervical Injection’, which involves injection into both right and left common carotid arteries, Mayer lists (p. 246) the easy removal of clots present in these arteries as an advantage of the method:

I have not found any reference to post-mortem clots in any artery other than the aorta and the common carotid in Mayer (nor indeed in any other source). In particular there is no reference to post-mortem clotting in the femoral artery and, to the contrary, a student of Mayer, having learned that the arteries are ‘generally empty of blood’ after death, could accordingly expect the femoral artery to be more or less empty of blood after free of post-mortem clots.

What does Mayer say about clots in connection with the use of the iliofemoral region as the injection site?

In a section on ‘Selecting an Artery as an Injection Point’, Mayer lists (p. 177) nine questions which the embalmer needs to consider, of which one concerns clotting:

As embalming fluid is injected at pressure into the artery, in what direction will any arterial clots be moved?

If the single-point injection technique is being employed, and the site chosen is the iliofemoral, then two injection tubes are inserted into the femoral artery, one towards the leg, and one towards the trunk (p. 190):

It is the tube directed towards the trunk that can create problems for the embalmer, accordign to Mayer. When he comes to consider how clotting affects the choice of injection site, he cautions (pp. 179) that if clots may be present in the arterial system, particularly in the aorta, then the femoral artery should not be used as the injection starting point:

since coagula could be pushed up (by the injection directed towards the trunk) into the common carotid or axillary arteries, which supply areas of the body (head and hands) which will be viewed:

This could only happen if the clots were between the femoral artery and the common carotid and axillary arteries. The aorta, from the abdominal aorta through the thoracic aorta to the arch of aorta, is the main vessel that connects them (Mayer 162):

and it is the aorta that Mayer has mentioned as a common location for clots.

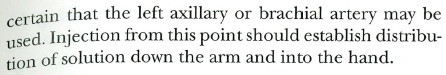

On the next page (180), Mayer gives a hypothetical example of what may happen if the femoral artery is used as the starting injection site. The embalmer finds that no embalming solution has reached the left arm. It is posited that a clot or coagulum has been moved from the abdominal aorta to the left subclavian artery (which leads into the left axillary). The embalmer’s response will be to use a secondary injection site to ensure that embalming fluid be distributed down the arm into the hand. Mayer says that it is ‘almost certain’ that the left axillary or brachial artery may be used, which seems to imply that it is very unlikely that there will be clots in the arteries of the arm since, if there were, injection at the axillary would likely also be more or less unsuccessful:

Once again, when Mayer comes, in a section on ‘Vessels used for arterial embalming’, to discuss (p. 189) the use of the femoral artery, the only point related to clots or coagula is the same one, namely that caution must be exercised in case they are pushed into the vessels that supply the arms or head:

At no point does Mayer suggest that clots may be found at the iliofemoral injection site. They would be found, if anywhere, in the aorta or, if moved by the embalming fluid injected at pressure, then beyond the aorta in the direction of the head and arms.

What does Mayer say about clots in connection with the use of the iliofemoral region as a secondary injection site?

Mayer states (p. 182) that the common carotid artery is the ‘best choice’ for injection site:

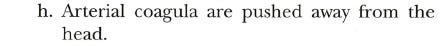

One of the reasons cited (p. 182) is that arterial coagula are pushed away from the head:

In the section on ‘Arterial Coagula’ in Chapter 22, Mayer states further (p. 424) that injecting the common carotid arteries will push arterial coagula, especially in the large aorta, ‘towards the legs’:

Again, in the same section, he states more specifically (p. 425) that arterial coagula will be moved into the iliac and femoral arteries:

making it clear that Mayer has in mind coagula situated between the common carotid artery and the iliac arteries, that is to say, in the aorta, or conceivably in the brachiocephalic artery.

If the embalmer becomes aware that this has happened, presumably because of a lack of distribution in tissue below points of blockage, then the femoral arteries can be used (p. 425) as a secondary injection site:

Mayer considers the possibility that even this would be unsuccessful, presumably because coagula had moved further down the leg than the injection point:

The same scenario, with the common carotid as the primary injection site, a lack of distribution in a leg, and the use of the femoral artery as a secondary injection point, is the subject of another of Mayer’s hypothetical short case studies:

If the leg itself were clotted raising the femoral artery would not solve the problem. What Mayer almost certainly has in mind are coagula, either located in, or originating in, the aorta, which prevent the embalming fluid reaching the femoral artery.

Schmidt appeals to this same scenario

Having claimed that the iliofemoral region is a ‘danger area for clots and arterial blockages’, as discussed above, Schmidt goes on to say that when these are encountered, it may be necessary to inject the femoral artery:

His use of the word ‘encountered’ suggests that he may have in mind a scenario that arises after fluid injection has begun, so that this would be a secondary injection at the femoral. This impression is strengthened by his following observation that it is often the case that more than one artery has to be injected to ‘complete’ the embalming, suggesting that the process has already begun and that this would be a secondary injection:

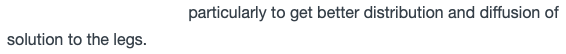

which could enable improved distribution and diffusion8 to the legs:

Schmidt seems to have in view the situation described above, with the primary injection at the common carotid, and a blockage caused by clots located between the injection point and the iliofemoral region. It is in this scenario that a secondary injection at the femoral could improve distribution to the legs.

All Schmidt has shown therefore is that clots are commonly encountered on the trunk side of an iliofemoral arterial incision. He presents no evidence or argument that it is normal to encounter clots on the leg side of such an incision. Since arteries narrow progressively away from the heart, any such clots in the leg arteries would presumably be small pieces broken off from larger clots in the aorta, of a very different character to the single long piece extracted by Hirschman.

As it happens, Hirschman extracted this material from the iliac before he had begun injecting embalming fluid at any location. He explained in an interview (0:37 ff) that he had noticed that there seemed to be some of this type of material in the vein before he made his incision. After extracting the material from the vein, and making an incision in the adjacent artery, presumably with a view to injecting in both directions, he noticed (0:00 ff) the material in the artery also. He had therefore no need to consider the possibility of encountering coagula that had been moved down from the aorta by an injection at the carotid.

Conclusions

Richard Hirschman extracted a long piece of whitish material from the leg arteries of a deceased person, commenting that it was unusual to find clots in the artery, and further that this particular material was not normal at all.

Benjamin Schmidt, ignoring the character of the material itself, claimed that if Hirschman had consulted an embalming textbook, he would have known that it was normal to encounter clots in the iliofemoral region.

Consultation of the leading embalming textbook, by Mayer, yields the following information:

1) The arteries are generally empty of blood after death. It follows that post-mortem clot will generally not be encountered in arteries.

2) Some blood does remain in the aorta, and this may coagulate.

3) Clots may also be found in the common carotid artery. No mention is made of clots in any other artery.

4) Clots in the aorta may move when embalming fluid enters it at pressure from one direction or another.

5) If the primary injection site is in the iliofemoral region, then clots may move towards the head and arms and cause arterial blockages, hindering distribution to areas that may be viewed.

6) If the primary injection site is the common carotid artery, clots may move towards the legs and cause arterial blockages, hindering distribution to the legs.

7) Secondary injection at the iliofemoral tend to be successful, implying that the blockages are most often on the trunk side of the incision.

8) While arteriosclerosis is common at the iliofemoral, its primary significance to embalmers is that any stenosis (narrowing) may hinder insertion of injection tubes. If stenosis leads to the capture of clots that have moved from the aorta, then these will likely be on the trunk side of the incision.

Mayer makes no explicit reference to clots being encountered in leg arteries. Injection from the common carotid could potentially move small pieces of clot from the aorta to the leg arteries, but in this particular case Hirschman had not begun injecting at all. Mayer teaches a general emptying of arteries after death, giving reason to expect an absence of post-mortem clot in the leg arteries. Hirschman was correct in saying that it was unusual to find clot in the leg artery, and the material that he did find and extract appears to have been extremely abnormal.

Andrew Chapman

It seems to me that there will be an increase of velocity at the point of constriction, this being an aspect of the Venturi effect.

O. Jawaid, E. Armstrong ‘Endovascular Treatment of Common Femoral Artery Atherosclerotic Disease’ Vascular & Endovascular Review 2018;1(1):12–6.

Lyaker MR, Tulman DB, Dimitrova GT, Pin RH, Papadimos TJ. Arterial embolism. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2013 Jan;3(1):77-87.

Zheng Li, Gerald H. Pollack, ‘On the Driver of Blood Circulation Beyond the Heart’, preprint, p. 7.

C.L. Barnes ‘The Art and Science of Embalming’ (Trade Periodical Publisher, 1896).

G. Valentin ‘A Textbook of Physiology’, tr. W. Brinton (London: 1853), p. 220. https://archive.org/details/atextbookphysio00bringoog/page/220. I have not so far found treatment of the subject in a modern textbook. M. Foster, Professor of Physiology in the University of Cambridge referred to the blood being emptied of blood at death: ‘A Text Book of Physiology’ (London, Macmillan: 1891) https://archive.org/details/cu31924050543143/page/n217

‘Distribution’ is movement throughout the arterial system and into the capillaries; ‘diffusion’ is movement through the capillary walls to the tissue spaces (Mayer, 257).

Excellent piece, Andrew. Thank you

What an absolute distraction from the biosynthetic soft actuators made through reverse opal hydrogel - whoever wrote all of this is either in denial or actively trying to corrupt the resistance movement with lies